Yellowstone’s Mud Volcano is among the most…uh…fragrant areas in the park. It’s worth the nasal assault, though, because the features fit the park’s secondary theme of weird. (With its acres and acres of astounding scenery, the park’s primary theme is, of course, wow!.) And if you’ve ever lived in a house with well water, the scent may be somewhat familiar to you. Likely a bit stronger than you’ve experienced, but familiar nonetheless.

The mud volcano itself — which apparently isn’t a “real” mud volcano, according to those snooty scientific folks; does that make it a fauxcano? — is among the first features on the area’s relatively short walking path. Years ago it shot mud into the air and thus actually resembled a small volcano, but eventually it became a victim of its own perpetual rage: one side of the volcano collapsed, leaving it looking more like a hot tub at Pig Pen‘s house.

The sign accompanying the volcano included an amusing account from the first American explorers to encounter the startling sight of mud shooting into the air. I don’t recall the sign well enough to recount it here, but as you might imagine, they were understandably perplexed: not only had they never seen such a sight, but they’d also never even heard of the possibility of the existence of such a sight. We have such a muckle of information available to us now that most natural phenomena are widely known or easily discovered, but that wasn’t the case 140 years ago.

As it turns out, the trail through the mud volcano area happens to be one of the better places to get an up close and person experience with a few of the park’s many bison. We became aware of that little tidbit when we turned a corner and saw two bison lounging near the trail.

They eyed us curious tourists with obvious disdain — just look at the bison’s expression in the first photo! — but fortunately, it was a lazy disdain. Had they wanted to make trouble, we would have had few escape choices, and all of them would have involved uncomfortably hot pools of mud or water. But they were content to munch on the grass, we were content to take photos, and the nearest hospital was content not to have patients with severe bison-related injuries.

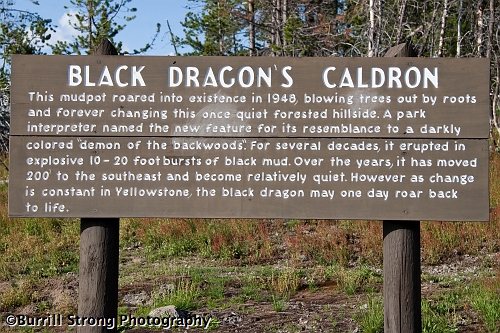

A few minutes down the trail from the volcano was a cluster of mudpots, which are more features in which you could cook pasta (though you shouldn’t actually try that, and I don’t know why you’d want to). The first and most prominent was Black Dragon’s Caldron, and it had its own sign recounting its own strange history.

If you can’t read the sign in the photo, it says: “This mudpot roared into existence in 1948, blowing trees out by roots and forever changing this once quiet forested hillside. A park interpreter named the new feature for its resemblance to a darkly colored ‘demon of the backwoods’. For several decades, it erupted in explosive 10-20 foot bursts of black mud. Over the years, it has moved 200′ to the southeast and become relatively quiet. However as change is constant in Yellowstone, the black dragon may one day roar back to life.”

Further along the trail were a few more mudpots that were considerably more agitated than the currently sedate Black Dragon’s Caldron.

Near the end of the trail was a large pool of reasonably placid water with a set of odoriferous neighbors:

The clouds of steam on the right side are coming from a few of the park’s four thousand fumaroles. They’re sort of like steaming manhole covers, except you might require medical attention if you walked over the top of a fumarole. They’re sort of warm in the same way that Yao Ming is sort of tall, Star Wars is sort of popular, and analogies are sort of easy to make.

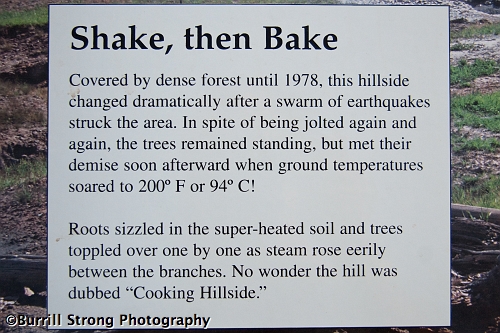

The area on the near side of that pool of water was covered with dead trees, a most curious fact helpfully explained by another informative sign:

If you can’t read the sign, it says: “Covered by dense forest until 1978, this hillside changed dramatically after a swarm of earthquakes struck the area. In spite of being jolted again and again, the trees remained standing, but met their demise soon afterward when ground temperatures soared to 200° F or 94° C!

Roots sizzled in the super-heated soil and trees toppled over one by one as steam rose eerily between the branches. No wonder the hill was dubbed ‘Cooking Hillside.'”

The trail ends back at the parking lot, and adjacent to the parking lot is another pool of piping-hot water.

When we reached the end of the trail, we found that the parking lot itself provided a fine example of the extraordinary heat produced by the park’s thermal features. The lot had the usual collection of drains to collect rainwater, but the features encroached underneath the pavement and turned one drain into just another vent for its carpet-cleaning steam. Park rangers placed a traffic cone on top of the drain to prevent visitors from parking or walking on the hot metal, but since the cone was rubber, it wilted under the relentless assault of the intense heat.