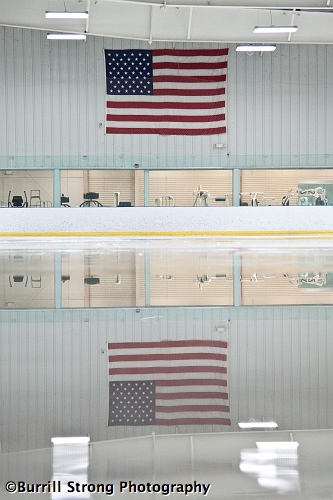

It is an unshakable fact of life that whatever can be built must also be maintained and, on occasion, replaced; since the sheets of ice found in ice arenas are manmade, it stands to reason that they, too, must be maintained and even occasionally replaced. For the average ice-aware individual, the maintenance and replacement of ice is shrouded in mystery; most people know about the iconic Zamboni ice resurfacing machines, but few know how a sheet of ice is built in the first place, and few get to see the whole ice replacement process from removal to reconstruction. But by the end of this series, the readers of this blog — and, later, the readers of the Chelsea Standard — no longer will be ignorant of that process: thanks to the crew at Chelsea’s Arctic Coliseum, I have the opportunity to observe and photograph the process from start to finish. Prepare to be illuminated!

Before I begin with the deconstruction photos, I should mention one important fact that may surprise you: as it is at many local rinks, the ice at Arctic is built on a foundation of sand. Though that might concern the Biblical scholars among us, it’s not nearly as tenuous as it sounds; in fact, it’s a common method of construction. You’ll get to see the sand for yourself in future posts, but since this is ice replacement, the whole process starts when there’s still ice in the rink.

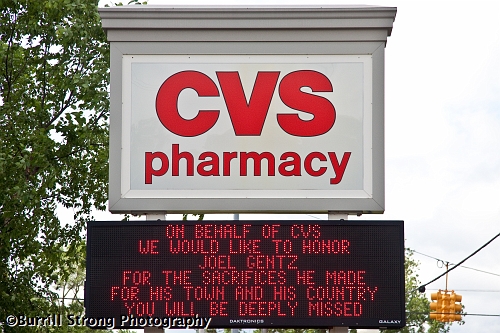

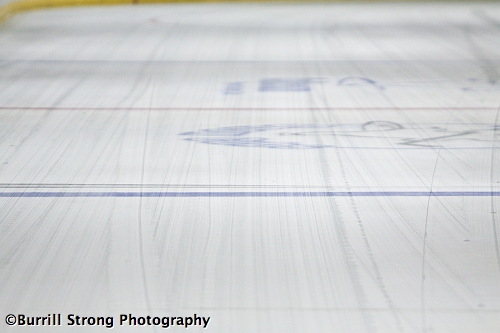

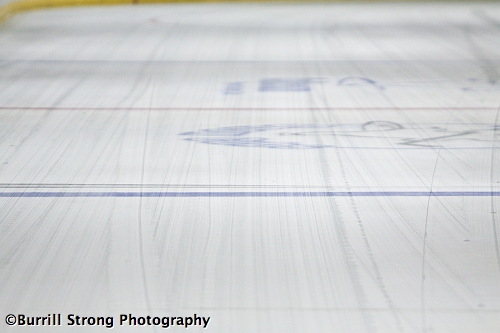

You may be wondering: why does the ice need to be replaced? Is it really that bad? Well…since they’re spending time and money to replace the ice, the answer is obvious: yes, it is that bad. The Coliseum’s other rink doesn’t have any serious problems, but this rink had developed large cracks that adversely affected ice quality.

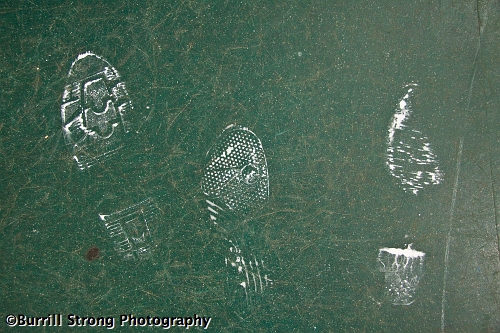

Though the cracks feel smooth on the surface, they’re problematic in at least two ways. First, they allow sand to work its way up into the ice and, eventually, to the surface, resulting in inferior ice for skaters and dulling the Zamboni blades more quickly; second, as visible above, they also pull the paint out of the ice and reveal the sand beneath the ice, making them uglier than a Matt Millen draft board. And just as the only way to fix a Millen draft is to replace Millen, the only way to fix cracks in a sheet of ice is to replace the ice.

Naturally, to replace the ice, you must first remove the ice. The first step is simply to cut the refrigeration and let the room warm up. What happens when the room warms up? The ice begins to melt, most visibly at the edge.

But while ice conveniently and predictably melts when it’s not properly refrigerated, it can take a while for that much ice to melt, and it can take even longer for that much water to evaporate. It doesn’t take long for the edge of the ice — seen at the Zamboni door in the above photo — to look slushy, but the rest of the surface keeps its cool much too well to let it disappear without encouragement. The good news is that it’s not difficult to encourage an ice surface to disappear.

There’s a misconception that Zambonis do little more than spread water on the ice to fill in its imperfections, but the process is far more complicated than that; in addition to spreading new water on the ice, they also shave off a layer of worn ice and clean the ice before adding a coat of new water. Those capabilities work together beautifully for resurfacing ice, but when it comes to removing ice, the machine need only channel its inner Norelco and give the ice a close shave.

(In case you were wondering, Arctic Coliseum uses real Zambonis, and not those inferior knockoffs Olympic organizers so foolishly used at the Vancouver Olympics.)

Most of the ice shavings are collected in the snow tank, but some are a bit less cooperative, electing instead to watch the process from a front-row seat near the Zamboni’s blade.

Despite their best efforts, those shavings still end up off the rink.

The remaining ice provides a good reason to appreciate the second and third steps in a Zamboni’s resurfacing process. Hockey wouldn’t be much fun on ice that had been shaved but not reconditioned:

Though it may not be difficult to remove ice with a Zamboni, it’s certainly time-consuming. That’s why you’ll still see Zambonis running on day 3.

Speaking of which: come back soon for the day 3 post, in which the ice rink begins to look less like an ice rink!